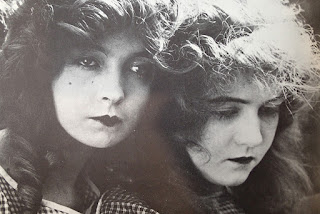

The Gish Girls Talk About Each Other - 1921 (Photoplay)

The Gish Girls Talk About Each Other

To

ADA PATTERSON (Photoplay Feb – Jun

1921)

"All

we have in common is our mother," said one of the most unlike sisters in

the world. Lillian Gish spoke. The young tragedienne whom John Barrymore has

called "The American Bernhardt" sat staidly in a chair according to

the accepted relation of chairs and sitters. Dorothy Gish, the comedienne, perched

on hers. It must be chronicled of Mrs. James Rennie that she sits on her feet.

She is more comfortable so and neither her sad-eyed sister, nor her mother, nor

her bridegroom ever reproves her for the acquired in childhood habit. It's a part

of her and none of the family wants to lose any part of Dorothy.

The

sisters had promised to talk about each other to me. They had agreed to tell

the truth, frankly, as they saw it. The time was a recent Saturday afternoon.

The place was the apartment occupied by Mrs. Gish and Lillian. Hard by was that

of the"7ecently made Mrs. James Rennie with her handsome young lord. Yes,

at the Hotel Savoy, although the address of the pair is 132 East Nineteenth

Street. "We give teas at the Nineteenth Street address but live

here," said the bride. "It will be so until we have thoroughly

furnished the apartment."

"What

do you think of your sister's marriage?"

Lillian

Gish of the wide, blue, thoughtful eyes, that register such depths of feeling

on the silver sheet, adjusted herself and the skirt of her girlish blue serge

suit on the gilt backed chair. "I approve it," she said. "It is

fine to have a man about the place. It is the first time in my recollection

that we have had one. Our father died when we were babies. It seems odd for Jim

to come in to breakfast in his Japanese kimono. I didn't know men wore such

things, at least in the morning."

"Japanese

kimonos? Yes, indeed, they're emphatically the thing," Mrs. James Rennie

assured her.

"You

think a man's handy to have about the house?"

"Yes,

to drive nails and tell you about stocks and bonds and to put the waiter in his

place," rejoined Miss Gish of the wide, wistful eyes.

"And

what do you think of your sister being single? Would you like to see her

married?"

"Yes,

why not?" Dorothy flashed her answer. She is as swift of speech as the tragedienne

is deliberate.

"Kipling

said something about travelling faster if you travel alone, didn't he?"

"I

don't believe that," from Dorothy.

"Didn't

Duse say that one should live life fully, round out one's existence with every

legitimate human experience? I stand with Duse. Still"—one of those little

grimaces that delight her

audiences,—"Lillian may become the old maid of the family.

Mother

always chided me because I had to go fishing for anything in my trunk or bureau

drawers. Lillian's bureau drawers and trunks are always models. If any of her

things were displaced,— or should I say. misplaced,—it would be a

calamity."

"Do

you ever quarrel.-'"

"No."

Lillian Gish spoke with her quiet, last-word-on-thesubject manner. "We

have never quarreled because we respect each other."

"Not

even when you directed your sister in a motion picture?"

"No.

We knew that each was working for the other's benefit. Dorothy followed my

directions as she would any other director's. We were both pleased with the

result. The picture, 'Remodelling a Husband,' was a good one. But I shouldn't

want

to be a director. I am not strong enough. I doubt if any woman is. I understand

now why Lois Weber was always ill after a picture. Directing requires a man of

vigor and imagination."

"What

are your points of greatest difference?"

"Dorothv

likes to go about. She mingles with people. I don't." Mrs. James Rennie

wagged her side-bobbed head. "I must be among people. I need them. I think

it helps me in my work. I watch how they do things and whatever I see comes

back to me when I am before the camera."

Lillian

Gish turned the blue depths of her eyes upon me. "I have given up going among

people," she said. "They interest me. But I have never been able to

keep engagements. I just love Mary Pickford. She often asked me out to her

place at Beverly'Hills. I would think I could go but at five o'clock when I

should have been

going

home to dress for dinner we would decide to work until seven. Something like that

always happened when I wanted to go out to see Mary. After your friends have asked

you five or six times and you have to telephone that you are very sorry but you

can't go, they stop asking. That is quite natural. And so I gave up going out.

I draw my ideas of how to do things from within. I think of how I would do

whatever I had to do if I were in the person's place."

"What

do you most admire in your sister?"

For

a moment Dorothy Gish's sparkling eyes took on depths of seriousness.

"Her

gentleness. Lillian never offends anyone." I met Lillian Gish's calm, blue

gaze in inquiry. "I most admire Dorothy's honesty. No one could make

Dorothy tell a lie. Sometimes, when cornered, I evade." Dorothy Gish

leaned far forward, clasping her small hands boyishly between her knees.

"But

people don't want to hear the truth. I've found that out. They have asked me

for

the truth and I've told them and hurt them. I wanted to help them but I only

hurt

them. I would love to have Lillian's diplomacy."

"What

is your ambition for your sister?"

"I

want to see Lillian on the stage. I believe she would be another Maude

Adams."

"Nobody

could be like Miss Adams. My admiration for her is boundless. But she will

always keep her niche. No one will ever be like her. Mr. John Barrymore, whom I

met the other day for the first time, assured me that screen work is harder

than stage work. But I don't know that I could ever develop my voice to the

strength for the stage. I want to see Dorothy progress in her comedy. Comedy is

a great deal harder than tragedy. Tragedy plays itself."

"No.

Besides, tragedy is what lives. No one remembers a comedy. But 'Broken Blossoms'

and 'Way Down East' will live," spoke Dorothy.

Even

their portraits differ. Lillian, with one of her rare, and rarely sweet, smiles

produced an old photograph of a rotund, serious child borne down, it would

appear, by a heavy weight of care.

"

This is Dorothy's picture when she was a baby. The family call it Grandma

Gish."

"Yes.

Look on this and then on that."

The

"that'' at which Dorothy Gish's brown head nodded was Helleu's portrait of

Lillian

Gish as he saw her, a mist of bluish grays, enswirling, cloud-like, a delicate

face with. deeply, widely blue eyes, of the soberness and inscrutability of the

Sphinx.

What

of the worldly wisdom of these young pet sons, that wisdom that has to do

with

the care of earned increment? "Dorothy likes to spend money," said

her sister. "Mother thinks I am the conservator of the Family funds.

Perhaps that is

true.

I have a deep, overwhelming fear of poverty. I look far into the future. I have

resolved

that when I am old I shall have more than one dress and three hundred

dollars."

"It

takes more than that to get into an old ladies' home now," said Dorothy.

" The

price

of old ladies' homes has gone up. It used to be $300. Now it's $500."

"You

know that, dear? Then remember it," admonished Lillian.

"We're

here today. Gone tomorrow. Let us enjoy today." Mrs. Rennie snapped

her

small fingers. Entered a slender, silver-haired woman, round of face like Dorothy, graceful and with wide, thoughtful

distance between the eyes, like Lillian. Both girls sprang to their feet. Both said:

"This is Mother.'

"She

isn't a bit like a stage or studio mother," testified Dorothy.

Through

her the talented twain derived their membership in the Daughters of the

American

Revolution and their eligibility to the Colonial Dames. Through her, too,

they

are kinswomen of the youngest Justice of the Supreme Bench of the United

States, Judge Robinson.

"You

were talking of saving and investing?"

said

Mis. Gish. "The family joke is that neither of my daughters cares for real

estate, while 1 crave it. We could have bought lots in Los Angeles for $250 a

piece a few years ago. I favored it but I was the minority. The lots have since

sold for $5000 a piece."

Lillian

lifted her head. "But if we had bought them we would have had the Gish luck.

That part of Los Angeles would not have improved li would have toed stock

still."

Bitterness?

No. Only a belief that the Gishes are not of those to whom delightful things happen. They must earn by toilsome ways

their profits and success.

They

drifted back into recollections of their still near childhood, "Lillian

used to put beans up her nose." From the mask of comedy.

"Dorothy

would nevet keep quiet. Once she was spanked for it." From the mask of

tragedy.

"Lillian

cried because I was spanked. She cried long after I had stopped. She could

always cry easily and make others cry in sympathy. She used to make the

neighbors cry just by looking at them. They all told mother she 'would never bring

that child up,' " Mrs. Rennie mimicked a toothless neighbor's mode of

speech.

At

four Dorothy made her debut in public gaze in "Last Lynne." At the

same time

her

sister, Lillian, at six, was playing the same tear-guaranteed part in another

company.

Returned

alter their barnstorming the sisters prattled of their tours and the wisdom

therefrom derived.

"And

now I'm a vegetarian," announced Sister Lillian.

"That's

nothing. I'm a Catholic," proclaimed Dorothy. Which was interesting though

not true.

Comments

Post a Comment