Women on the Hollywood Screen – By Frank Manchel (1977)

Women on the Hollywood Screen – By Frank Manchel (1977)

Women on the Hollywood Screen

By Frank Manchel – 1977

America’s fantasies, hopes, and fears can be seen in the changing roles of women in films. As the values of an era change, filmmakers adjust the image of women to fit in with the new social climate. In the movies of each decade there is a hidden story about women which the author traces, from the early years, through the Hollywood heyday of the thirties, and up to the present crisis faced by women in films and society today.

The first movies educated our great- grandparents about a woman’s place in society. Such actresses as Mary Pickford and the Gish sisters showed the “right” way for young ladies to behave—they focused on loving their men and children, on being gentle, religious and sensible. In contrast there was Theda Bara, known as “the Vamp,” whose screen roles proved that sex was dangerous. During the Twenties, a new ‘liberated’ woman appeared—the flapper. In films glorifying youth and love, such actresses as Clara Bow spoke to the new woman in society who smoked, bobbed her hair, went to work, and had her own money to spend. Then came the Thirties and the Great Depression. Most Americans turned to the new talking pictures to escape from the boredom and insecurity of their everyday lives.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Frank Manchel is a graduate of Ohio State University and is presently professor of communications and theater at the University of Vermont where he teaches several courses in the history and appreciation of film. Dr. Manchel has lectured widely and written for many professional journals in the areas of film and education. He is the author of numerous books for young readers dealing with film history, including Yesterday’s Clowns: The Rise of Film Comedy, The Talking Clowns: From Laurel and Hardy to the Marx Brothers, and An Album of Great Science Fiction Films, published by Franklin Watts, Inc.

Saints and Sinners

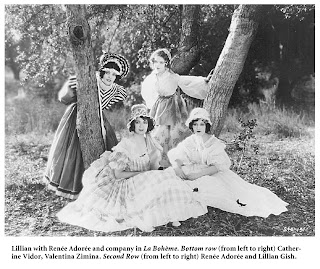

Lillian Gish was the silent era’s greatest actress and the ideal symbol of young womanhood. For Griffith, Gish and the other stars he directed served to remind the public of the old days. Her finest role, as True Heart Susie (1919), is pictured here.

Lillian Gish was another star who kept sex and passion in the background. In Way Down East (1920), she and D. W. Griffith proved that the public still valued the old social code. As the twenties wore on, however, Gish’s gentle beauty no longer appealed to fans more interested in sexy heroines.

For those movie fans who cherished the old values there was still Mary Pickford. Twice in the twenties she tried to play adult roles, but the films died at the box office. Thus the public “forced” her to remain childlike in films like Little Annie Rooney (1925).

Greta Garbo proved to be the timeless star. Audiences found in her the perfect lover. In Flesh and the Devil (1926), Garbo was a doomed wife whose love for another man leads to tragedy. John Gilbert played the part of her lover.

Fame and Fortune

The Hollywood woman underwent sweeping changes in the thirties.

It started with the sound revolution. By 1930, many silent screen stars had failed to switch successfully to the “talkies.” Among the more famous were Pola Negri, Clara Bow, Gloria Swanson, Lillian Gish, and Mary Pickford.

Some had never learned to act. Their fame had rested on their physical beauty alone. Others had bad movie voices; they didn’t sound the way they looked. Some, too rich to care about learning new methods of film acting, retired. Others couldn’t shed their “flapper” or “child-woman” images.

The failure of so many actresses brought forth a new type of screen star. She had to be able to act. Directors could no longer talk to her during the shooting of a scene. The sound cameras picked up any noise on the set. Talkies made characters more lifelike. Performers had to be able to handle dialogue, to speak and to act realistically. Many of the new stars, therefore, came from Broadway. Some of the best were Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Barbara Stanwyck, and Joan Blondell.

The radical changes in society also affected the fortunes of the Hollywood woman. The collapse of the stock market in late 1929 had started the Great Depression. By the early thirties an economic plague was sweeping across the country. Banks closed. Factories shut down. Unemployment sky-rocketed to the fifteen-million mark. In the richest country in the world people were walking around homeless and hungry.

Thus the first talkies tried to give women relief from the harsh realities of their everyday life. Musicals were the rage. Stories about poor girls who found fame and fortune on the stage served two purposes. First, musicals amused audiences with the novelty of all-talking, all-singing films. But second and more important, it turned the Hollywood woman into a glamour queen. She wore stunning gowns and traded wisecracks with the opposite sex. Musicals stressed that success depended upon a woman’s using her brains. Of course, the glamourous stars weren’t ‘real,’ but they did provide jobless women and tired housewives with a form of escape. For a few hours at least, a woman could daydream about fancy clothes, she could fantasize about a more exciting life.

The first talkies also reminded women of their roles as sex objects in a man’s world. Nowhere was this more clearly shown than in the Depression’s gangster films. Studios turned the daily headlines about bloody gang wars into blistering movies about the underworld. Women played a special part in every mobster’s life. As “Little Caesar” or “Scarface” rose to the top, he found a sexy gun moll urging him on. She went along with the easy money and the high living. But in reality, the women in such movies acted as a prize, not a person.

Such roles only pointed out women’s helplessness in society. The Depression made it clear that men were considered more important. Women couldn’t belong to unions, didn’t receive equal pay for the same work done by men, and marriage eliminated them from certain teaching positions if a man needed the same job. By the end of the thirties, more than 20 percent of all working women were unemployed.

Yet it was that sense of helplessness that gave the Hollywood woman her first of two golden ages in the decade.

Studio heads wisely decided to put their glamour queens in Depression roles. The idea was to show them living in poverty and shame.

Comments

Post a Comment