Artificial Archaeology And The Cinema – Griffith’s Intolerance By Drew (2008)

Artificial Archaeology And The Cinema – Griffith’s Intolerance By Drew (2008)

May 7, 2008, 10:24 pm

The cinema has always had an interesting practical relationship with archeology in addition to a more obvious influence its image in popular culture. Who doesn’t think of Indiana Jones when archeology is in the news- despite the fact that the good Doctor Jones never had to fill out all the forms and paperwork involved with Cultural Resource Management before hacking his way through primordial jungle, or even complete a single grant application to actually pay for his map-overlayed flight to Peru. It is interesting to compare the differences between the actual processes involved in archeology, and the ways archeology is depicted– a false archeology- addressed through the cinema in a new way, both creating an actual, pseudo-ruin and a realistically artificial image of Babylon.

(the capture of Babylon by Cyrus the Great from Intolerance– the sets are full size, and, besides limited matte/model work and forced perspective, has little in the way of what we would call ‘special effects’- just old fashioned camera trickery and genius accountants at work)

Perhaps the best example of this ‘false archeology’ can be found in D.W. Griffith’s silent classic Intolerance. Equally a response to the criticism of his earlier work, Birth of a Nation, (the racist content of which reinvigorated the KKK from the shell of its post-Reconstruction strength to a menacingly popular organization from the 1920s onwards- the film had even originally been titled The Clansman) and an attempt to ‘top’ what had been his greatest success, the film, through four intertwined, historical stories (the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, Capture of Babylon, Crucifixion of Jesus, Contemporary America) “shows how hatred and intolerance have struggled, through the ages, against love and charity”. The result is intriguing: a gigantic, brilliant, financial flop of a film depicting the cruelty of hatred, directed by a man most famous for ending his previous film with the Klu Klux Klan rescuing Lillian Gish from marrying a black man by ‘riding to the rescue’, taking away guns from black men, and then keeping them from voting. President Wilson, upon seeing Birth of Nation, supposedly said it was “like writing history with lightning.” So much for the Fourteen Points.

If it is possible to look at the film from a technical perspective, it was groundbreaking in terms of it’s filming methods and editing style. It is odd to think that other technically impressive films with unsavory overtones, such as the famously pro- Nazi box-office blitzkriegs Triumph of the Will and Olympia, are lauded for their creative achievement and at the same time reviled for their content. Birth of A Nation wasn’t an exception: it was incredibly controversial even when it was first released, and he did recut the film in 1921 to remove explicit reference to the KKK- of course, after everyone in America had already seen it. Intolerance was to be different- even more groundbreaking, epic in scope, and with a positive message that couldn’t detract from Griffith’s reputation. The film’s sprawling, four part story was made possible only by the financial success of Birth of A Nation, but despite this hefty bankroll, the film faced huge budget problems throughout its production, largely a result of the sheer scale of the project.

The four different sequences aren’t given equal time or attention- after all, who wants to see Contemporary America and it’s problems when you can watch saucy, nearly-nude dancing girls and sumptuous scenes of conquest. The unabashed center of Intolerance is the Babylon sequences. Forget CGI cityscapes and lily-livered greenscreening: Intolerance‘s set design is the most incredible feat of directorial chutzpah, Hollywood financial wizardry, and genuine craftsmanship ever produced by the cinema- an honest to god attempt at making a full scale replica of Babylon. The Babylon sequences are given the most screen time and directorial attention, and serve to bind the overarching story- the fall of the city is the film’s most compelling scene as Griffith’s innovative camera lingers on the city as the invaders storm the huge set. Hollywood has done nothing to equal this- even Ben-Hur’s chariot scene pales in comparison to the humongous Babylon set.

(Babylon as seen in Intolerance, restored photo

(Ishtar Gate from the walls of ancient Babylon, now in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.)

(The walls of Babylon as they appear today)

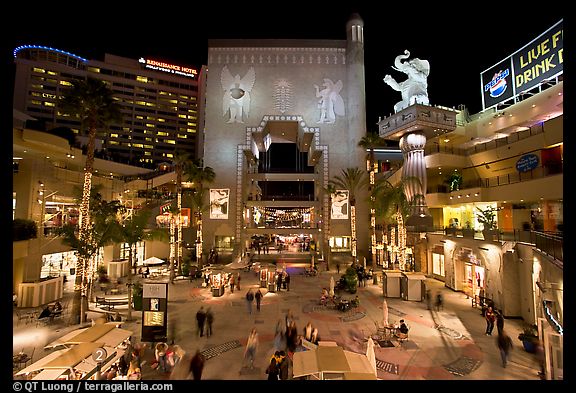

(This Moloch Machine is In keeping with the same fine American tradition that has created a miniature New York City inside a city built in the middle of the barren wastes of the Nevada desert- Las Vegas. Designed to liberate tourists from the burdens of their capital through the wiles of chain restaurants and shopping, this mall, in Los Angeles @ Hollywood and Highland, is directly based upon the Intolerance set [note the elephant on top of the pedestal on the right]

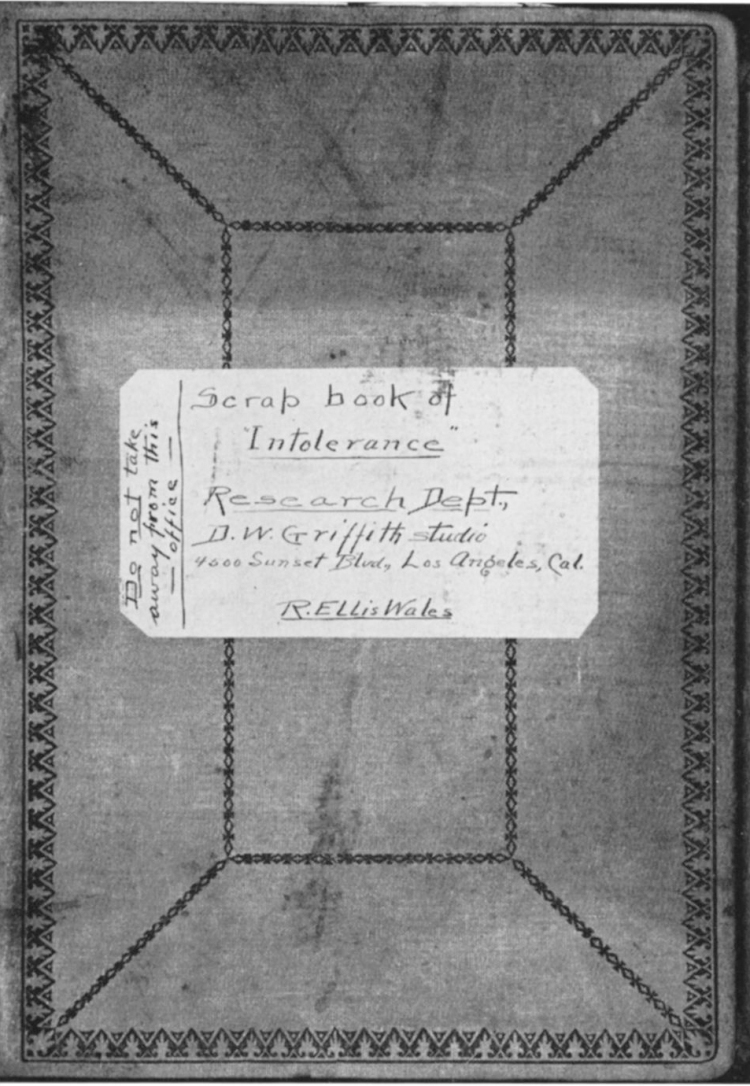

It would, for obvious reasons, be difficult to argue that Griffith’s Intolerance is a literal archaeological history- the sets and costumes, realistic as they might appear, have as much to do with the actual history of Babylon as Schliemann‘s pillage of of golden treasure has in common with 2004’s excuse to unleash notoriously old man Peter O’Toole and horrendously accented Brad Pitt in Troy. Intolerance is largely a conjecture, a mix of actual archeology and the imagination of a particularly gifted art design. The film was extensively researched by Griffith, who insisted on a high degree of realism- or at least the appearance of realism, in the set design. Objects in the film were usually based off actual, excavated objects- academic books were flipped through ad nauseum, and, most interestingly, a huge scrapbook of sources was compiled exclusively for the film’s art design:

“There is, however, a good deal of evidence in the film itself to show that considerable research was done in such areas as history, architecture, furniture, costumes, and the decorative arts. Outside the film there are records and anecdotes which testify to the research done for both archeological accuracy and aesthetic effects in the film. In addition to these sources of information, there is, in the Griffith Archives of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, a scrapbook compiled specifically for Griffith’s use during the filming of the Babylonian sequence of Intolerance.” {Hanson 496}

(Several pages from Griffith’s scrapbook on Intolerance– illustrations were often directly cut out from academic books and organized in the scrapbook by a dedicated team that worked personally with Griffith on the whole project.)

However, the demands of the camera could, and did, take precedence over the realism of the scrapbooks. Specific costume items had to be personalized for the actor or actress who would wear the garment. Stylization was allowed with some of the props, using the talents of the film’s incredible art design team (which Griffith directly led, having two Lead Designers on the film) to make certain particular objects were a bit more glamorous and attractive- after all, this is Hollywood Movie Magic we’re talking about, not some schmoe AIP vampire flick.

One architectural item in particular Griffith wanted in the film were elephants on top of the Babylonian city’s columns, perhaps inspired by an earlier Italian silent film on the ancient Carthaginians, Cabiria (1914). This connection between Griffith, who has been alternately rehabilitated and condemned for Birth of a Nation, and Cabiria‘s director, Gabrielle D’Annunzio, is somewhat odd, since D’Annunzio faced similar PR nightmares for being one of the first fascists in Italy, serving alternately as mentor and rival to Mussolini, and briefly conquering the city of Fiume and turning it into perhaps the strangest country emerge from WW1, with it’s fundamental principle being ‘music’. Epic films must attract epic egotists to their helms.

“Joseph Henabery recalls very well Griffith’s insistence upon the inclusion of elephants in the Intolerance set. Griffith was very keen on those elephants. He wanted one on top of each of the eight pedestals in Belshazzar’s Palace. I searched through all my books. ‘I’m sorry’, I said, ‘I can’t find any excuse for elephants. I don’t care what Dore’ or any other biblical artist has drawn- I can find no reason for putting elephants up there. To begin with, elephants were not native to this country. They may have known about them, but I can’t find any references.’ Finally, this fellow Wales found someplace a comment about elephants on the walls of Babylon, and Griffith, delighted, just grabbed it. He very much wanted elephants up there!” {Hanson 500}

The Intolerance set came to resemble an architectural model on a huge scale, albeit not a particularly accurate one. It’s sheer scale was overwhelming- massive, truly expansive, a monument in its own right, except it honored Griffith and the cinema instead of the Kings of Babylon- similar structures built more than a thousand years apart for entirely different purposes. The set strove for a ‘heightened’ realism- it was aggressive in its authenticity, but was still altered and changed from the ‘true’, architectural building it aped to make it appear more realistic through the camera’s moderated eye. The set of Intolerance was an imperfect doppelganger, an artificial archeology that reflected the grand idea of Babylon more than its more practical reality.

Despite the set of Intolerance being, by its very nature, fake, it actually became an actual archeological ruin of a certain nature, for at least a short while. The huge costs of the film made dissembling the set impossible, since labor costs had already been overrun so heavily and Hollywood studios are, if anything, hesitant to sink more money into a film that has already been released. The film’s box office was also somewhat less than expected, although the film eventually did turn a profit- audiences weren’t very taken with the complicated four-part plot, preferring to spend their money on tamer fare that was less preachy. As a result, the set lay abandoned since the producers refused to spend more money to destroy their fake city. Thus, for a time, Los Angeles had an abandoned Babylon within its borders, quickly deteriorating in the wind and weather as the cheap production processes set design use as their trademark slowly came undone. It soon became something of a tourist attraction, despite its worsening condition, and the city’s frequent fines.

An abstract question presents itself- had some disaster befallen the Earth in the winter of 1916, destroying our civilization in some sort of surreal, divine punishment for the forthcoming sins of flappers and Art Deco, would future archaeologists, coming across a ruined Babylon in sunny Los Angeles, have believed Hammurabi’s code had been proclaimed on the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard instead from ancient Iran? Eventually, the set for Intolerance burned down in the 1920s, either as an accident or through the actions of producers still hesitant to spend money on removing the huge structure.

(The abandoned set to Intolerance rots away in Los Angeles after the film has finished shooting, but before a fire destroyed the structure)

Hanson, Bernard. ‘D.W. Griffith: Some Sources.’ The Art Bulletin, Vol. 54, No. 4, 1972.

Comments

Post a Comment